2.1 Set Theory

Sets

A set is a collection of things.

The things are called elements of a set.

\[ Colors = \{\text{Red}, \text{Blue}, \text{Green}\} \]

\[ Numbers = \{1,2,3\} \]

Sets can be finite or infinite.

\[ Some\ Even\ Integers = \{2,4,6\} \]

\[ All\ Even\ Integers = \{..., -4, -2, 0, 2, 4, ...\} \]

The number of elements in a set is called the cardinality.

\[ |Colors| = 3 \]

Two sets are equal if they share exactly the same elements.

\[ A = \{2,4,6\}, B = \{4,2,6\}, C = \{4,2,7\} \]

\[ A = B \] \[ A \neq C \]

To express that \(2\) is an element of \(A\), we denote:

\[ 2 \in A \] \[ \text{2 exists in A} \]

\[ 5 \notin A \] \[ \text{5 does not exist in A} \]

Some sets are so significant that we reserve special symbols for them:

\[ \emptyset = \{\} \quad \textbf{(empty set)} \]

\[ \mathbb{N} = \{1, 2, 3, ... \} \quad \textbf{(natural numbers)} \]

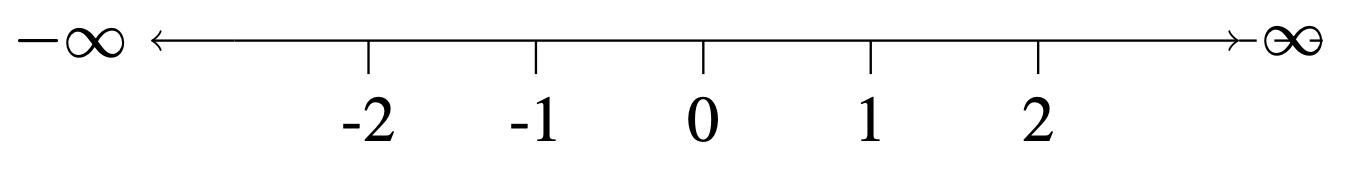

\[ \mathbb{Z} = \{..., -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, ... \} \quad \textbf{(integers)} \]

\[ \mathbb{R} = \{..., -0.22,...,0,...,1,..., \pi, ... \} \quad \textbf{(real numbers)} \]

We visualize \(\mathbb{R}\) as an infinitely long number line.

Set-Builder Notation

A special notation called set-builder notation is used to describe sets that are too big or complex to list between braces.

\[ All\ Even\ Integers_{1} = \{..., -4, -2, 0, 2, 4, ...\} \]

\[ All\ Even\ Integers_{2} = \{2x: x \in \mathbb{Z} \} \]

\[ \text{The set of all numbers of the form } 2x \text{ such that } x \in \mathbb{Z} \]

\[ All\ Even\ Integers_{1} = All\ Even\ Integers_{2} \]

Write the following sets in set-builder notation:

- \(\{ 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, ... \}\)

- \(\{ 0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, ... \}\)

- \(\{ 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 \}\)

- \(\{ 2^x: x \in \mathbb{N} \}\)

- \(\{ x^2: x \in \mathbb{Z} \}\)

- \(\{ x \in \mathbb{Z}: 3 \le x \le 8 \}\)

Subsets

Suppose \(A\) and \(B\) are sets.

If every element of \(A\) is also an element of \(B\), then we say \(A\) is a subset of \(B\), denoted \(A \subseteq B\).

We write \(A \not\subseteq B\) if \(A\) is not a subset of \(B\), that is, if it is not true that every element of \(A\) is also an element of \(B\).

Thus \(A \not\subseteq B\) means that there is at least one element of \(A\) that is not an element of \(B\).

\[ \mathbb{N} \subseteq \mathbb{Z} \subseteq \mathbb{R} \]

\[ A = \{1,2\}, B = \{2,3,4\} \] \[ A \not\subseteq B \]

List all the subsets of the following sets:

- \(\{1,2,3\}\)

- \(\{1,\{2,3\}\}\)

- \(\{\mathbb{N}, \mathbb{Z}, \mathbb{R}\}\)

- \(\{\}, \{1\}, \{2\}, \{3\}, \{1,2\}, \{1,3\}, \{2,3\}, \{1,2,3\}\)

- \(\{\}, \{1\}, \{\{2,3\}\}, \{1,\{2,3\}\}\)

- \(\{\}, \{\mathbb{N}\}, \{\mathbb{Z}\}, \{\mathbb{R}\}, \{\mathbb{N},\mathbb{Z}\}, \{\mathbb{N},\mathbb{R}\}, \{\mathbb{Z},\mathbb{R}\}, \{\mathbb{N},\mathbb{Z},\mathbb{R}\}\)

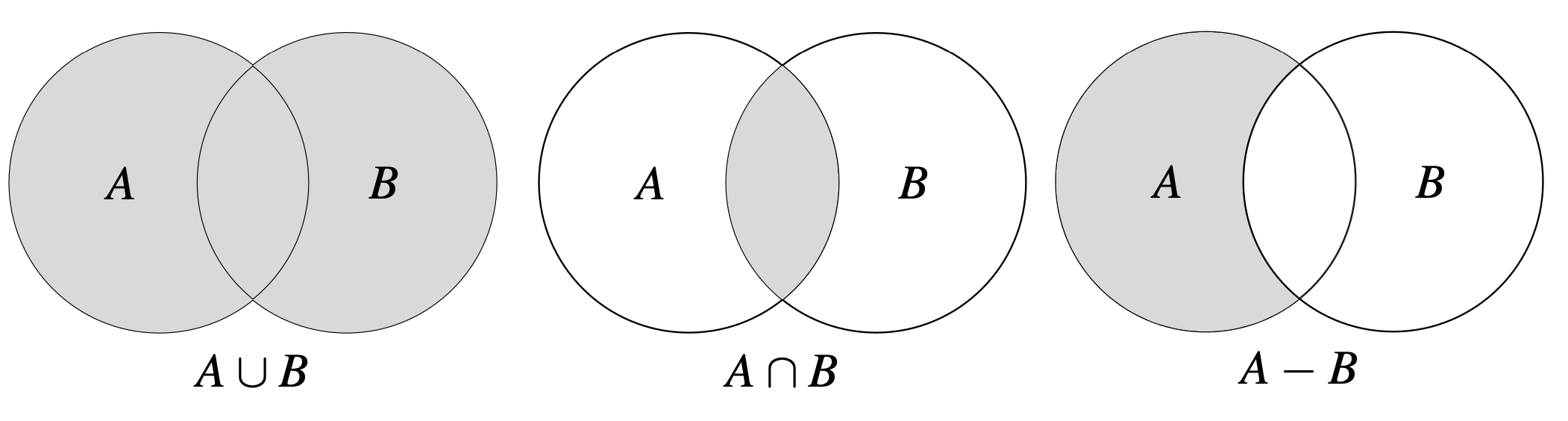

Union, Intersection, and Difference

Suppose \(A\) and \(B\) are sets.

A union of \(A\) and \(B\) is the set: \[ A \cup B = \{x: x \in A \text{ or } x \in B \} \]

A intersection of \(A\) and \(B\) is the set: \[ A \cap B = \{x: x \in A \text{ and } x \in B \} \]

A difference of \(A\) and \(B\) is the set: \[ A - B = \{x: x \in A \text{ and } x \notin B \} \]

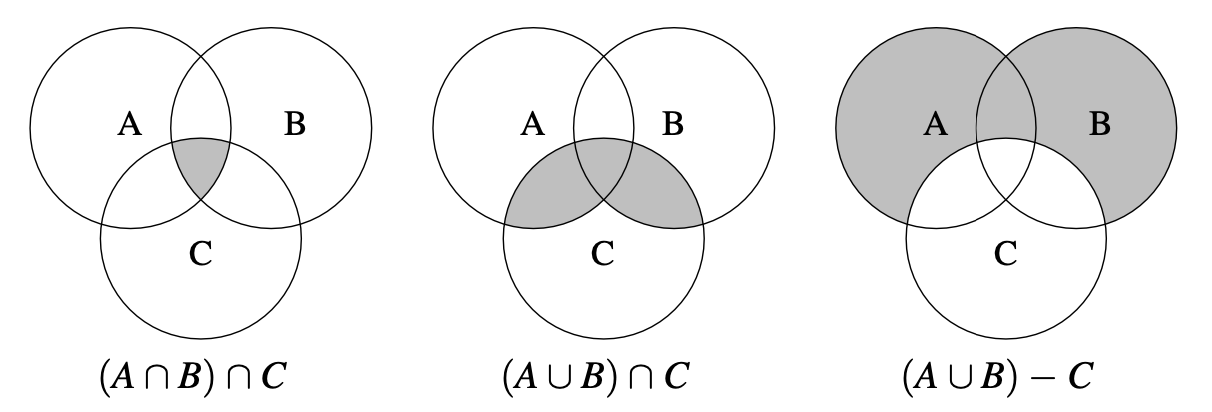

Shade in the region matching the expression:

- \((A \cap B) \cap C\)

- \((A \cup B) \cap C\)

- \((A \cup B) - C\)

Complements

Suppose \(A\) is a set.

A universal set is a larger set that encompasses other sets.

The complement of \(A\), denoted \(\bar{A}\), is the set \(\bar{A} = U - A\).

\[ P = \{2, 3, 5, 7, ...\} \quad \textbf{(prime numbers)} \]

\[ \bar{P} = \mathbb{N} - P = \{1, 4, 6, ...\} \]

Find \(\bar{A}\):

\[ A = \{1,2,3\}, U = \{0,1,2,3,4,5\} \]

\[ \bar{A} = \{0, 4, 5\} \]

Ordered Pair

An ordered pair is a list \((x,y)\) of two elements \(x\) and \(y\), enclosed in parentheses and separated by a comma.

\[ (1,2) \] \[ (2,1) \]

However:

\[ (1,2) \neq (2,1) \]

Cartesian Product

Suppose \(A\) and \(B\) are sets.

A cartesian product is simply the multiplication of sets denoted as \(A\) x \(B\) and defined as

\[ A x B = \{(a,b): a \in A, \ b \in B \} \]

\[ A = \{a, b, c\}, \ B = \{1, 2, 3\} \]

\[ A \ \text{x} \ B = \{ (a,1), (a,2), (a,3), (b,1), (b,2), (b,3), (c,1), (c,2), (c,3) \} \]

Ordered tripples such as \((x,y,z)\) are also possible.

\[ A = \{a, b\}, \ B = \{1, 2\}, \ C = \{I, II\} \]

\[ A \ \text{x} \ B \ \text{x} \ C = \{ (a,1,I), (a,1,II), (a,2,I), (a,2,II), (b,1,I), (b,1,II), (b,2,I), (b,2,II) \} \]

Cartesian Power

A cartesian power is also possible for any integer \(n\) as

\[ A^n = A \ \text{x} \ A \ \text{x} \ ... \ \text{x} \ A = \{ (x_1, x_2, ..., x_n):x_1,x_2,...,x_n \in A\} \]

One famous cartesian power is \(\mathbb{R}^2\), also known as the cartesian plane or a two-dimensional plane.

\[ \mathbb{R} \ \text{x} \ \mathbb{R} = \mathbb{R}^2 \]

\(\mathbb{R}^3\) three-dimensional planes are also possible.

\[ \mathbb{R} \ \text{x} \ \mathbb{R} \ \text{x} \ \mathbb{R} = \mathbb{R}^3 \]

And we can generalize up to \(n\) dimensions.

\[ \mathbb{R} \ \text{x} \ \mathbb{R} \ \text{x} \ ... \ \text{x} \ \mathbb{R} = \mathbb{R}^n \]

In Data Science, we often work in high-dimensional spaces—sometimes with thousands or even millions of dimensions. GPT-4, for example, is rumored to have over a trillion \(\mathbb{R}^{1,000,000,000,000,000}\).

For the following sets list the elements of their corresponding cartesian product:

\(A = \{1,2,3\}\) \(B = \{1, (2,3) \}\) \(C = \{\mathbb{Z}, \mathbb{R}\}\)

- \(A\) x \(B\)

- \(A\) x \(C\)

- \(A \ \text{x} \ B = \{ (1,1), (1,(2,3)), (2,1), (2, (2,3)), (3,1), (3,(2,3)) \}\)

- \(A \ \text{x} \ C = \{ (1,\mathbb{Z}), (1,\mathbb{R}), (2,\mathbb{Z}), (2,\mathbb{R}), (3,\mathbb{Z}), (3,\mathbb{R}) \}\)