4.1 Markov Chain

We saw from Lecture 3 how to make optimal decisions in non-associative environments:

\(\pi: S, A_{0}, R_{1}, S, A_{1}, R_{2}, ... , S, A_{T-1}, R_{T}\)

How can we learn to act optimally with changing states?

A associative environment is a setting that involves learning how to act in multiple states.

The best frameworks to generalize associative environments are Markov models.

All Markov models assume the Markov Property, meaning that future states depend only on current states and not previous states.

\[ P(s’ | s, s_{t-1}, s_{t-2}, \dots) = P(s’ | s) \]

Markov models differ based on whether every sequential state is observable and whether the system is adjusted based on observations:

| States are fully observable | States are partially observable | |

|---|---|---|

| Decision-making is not controlled | Markov Chain (MC) | Hidden Markov Model (HMM) |

| Decision-making is controlled | Markov Decision Process (MDP) | Partially Observable Markov Decision Process (POMDP) |

While Markov Chains model state transitions, they provide the foundation for defining value functions once rewards and actions are introduced.

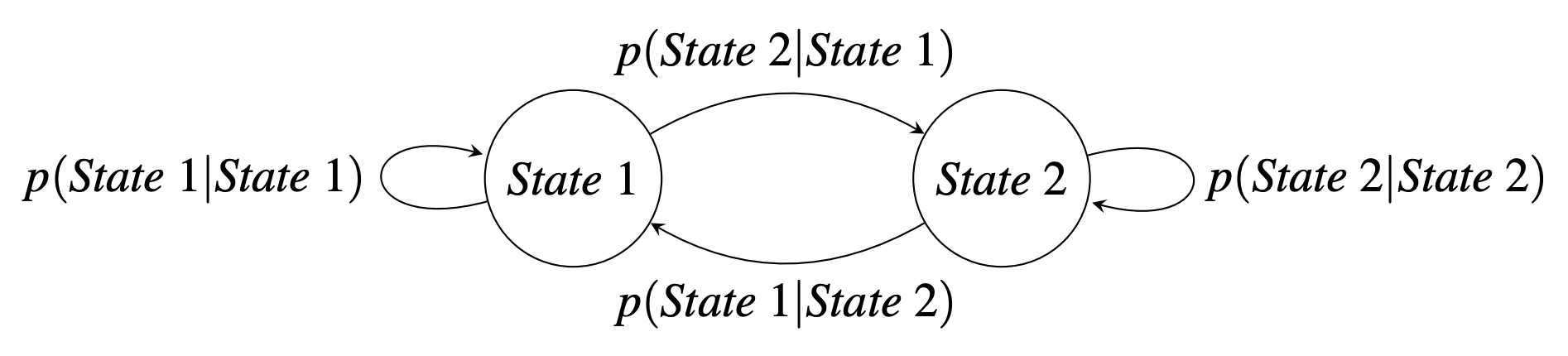

Markov Chain

A Markov Chain is a model for transitions that are not controlled between fully observable states.

A State is a node.

A State Transition is one outward-going arrow.

State transitions are conditional probabilities of going to the next state given the current state.

In this framework, we are interested in how state probabilities evolve over time and the corresponding values of each state.

Probability Matrix

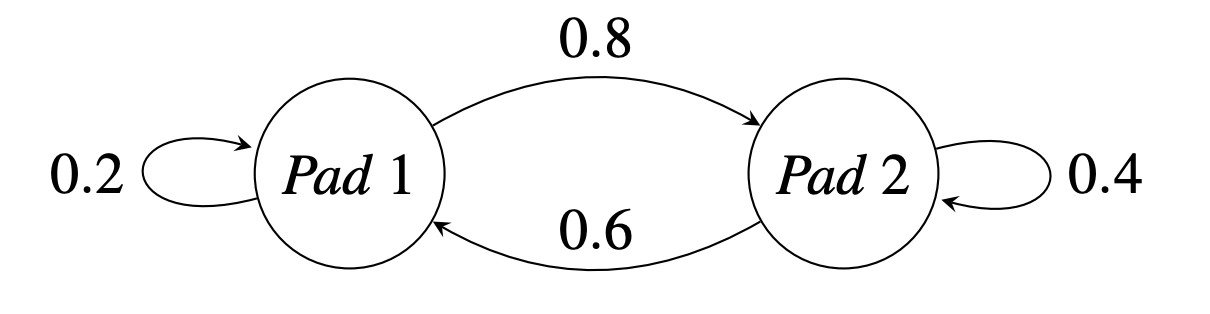

Suppose a frog jumps from one lily pad to another with state transition probabilities:

\[ \mathbf{P} = \begin{bmatrix} 0.2 & 0.6 \\ 0.8 & 0.4 \end{bmatrix} \]

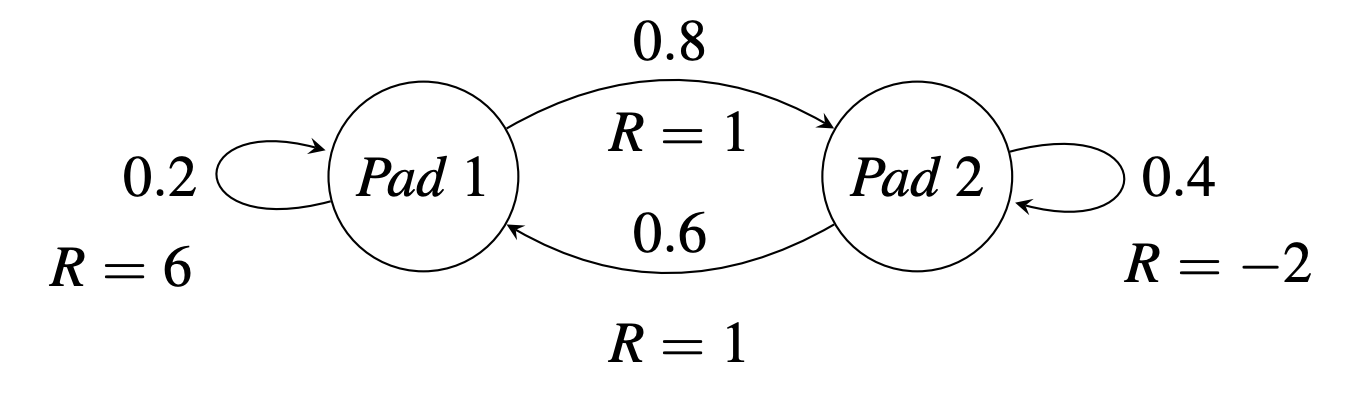

Rewards Matrix

Suppose the frog has associated rewards:

\[ \mathbf{R} = \begin{bmatrix} 6 & 1 \\ 1 & -2 \end{bmatrix} \]

Value Function

We want to calculate the expected value of moving from state \(i\) to state \(j\) for all situations \(s \in \{1,2,...,S\}\):

\[ \mathbf{v}(t) = \mathbf{q} + \mathbf{v}(t-1) \mathbf{P} \]

\[ \begin{align*} v_{j}(t) & = \sum_{i=1}^{S} p_{i,j} \ [r_{i,j}+v_{i}(t-1)] \\ & = \sum_{i=1}^{S} p_{i,j} \ r_{i,j} + \sum_{i=1}^{S} p_{i,j} \ v_{i}(t-1) \\ & = \textbf{q} + \sum_{i=1}^{S} p_{i,j}\ v_{i}(t-1) \end{align*} \]

First, we need to calculate \(\textbf{q}\), the expected reward in the next transition out of state \(i\):

\[ \textbf{q} = \begin{bmatrix} 2 & -0.2 \end{bmatrix} \]

\[ \mathbf{q} = \sum_{i=1}^{S} p_{i,j} r_{i,j} \]

\[ q_{1} = p_{1,1} \ r_{1,1} + r_{2,1} \ p_{2,1} \]

\[ q_{2} = p_{1,2} \ r_{1,2} + r_{2,2} \ p_{2,2} \]

\[ \begin{bmatrix} v_{1}(t) \ v_{2}(t) \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 2 \ -0.2 \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} v_{1}(t-1) \ v_{2}(t-1) \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 0.2 & 0.6 \\ 0.8 & 0.4 \end{bmatrix} \]

At \(t=100\): \[ \mathbf{v}(100) = \begin{bmatrix} 77.88 & 76.59 \end{bmatrix} \]

In other words, the frogs expected value at \(t = 100\) is that lilly pad \(1\) will be greater (with \(77.88\) expected flies) than that of lilly pad \(2\) (with \(76.59\) expected flies)

Discounting Factor

The \(\gamma\) allows us to place a higher value on the present rewards, rather than future uncertain rewards.

\[ \mathbf{v}(t) = \mathbf{q} + \gamma \mathbf{v}(t-1) \mathbf{P} \]

\[ \begin{bmatrix} v_{1}(t) \ v_{2}(t) \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 2 \ -0.2 \end{bmatrix} + \gamma \begin{bmatrix} v_{1}(t-1) \ v_{2}(t-1) \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 0.2 & 0.6 \\ 0.8 & 0.4 \end{bmatrix} \]

At \(\gamma=0.9\) and \(t=100\): \[ \mathbf{v}(100) = \begin{bmatrix} 8.47 & 7.15 \end{bmatrix} \]

Python Code

import numpy as np

GAMMA = 0.9

P = np.array([[0.2, 0.6], [0.8, 0.4]])

R = np.array([[6, 1], [1, -2]])

q = np.sum(P * R, axis=1)

v_initial = np.array([0, 0])

def value_function(v, P, q, t=100):

for _ in range(t):

v = q + GAMMA * np.dot(v, P)

return v

v_result = value_function(v_initial, P, q)

print(v_result)